The subtitle of Darra Goldstein’s new book Beyond The North Wind is Russia In Recipes And Lore. This makes it clear that the book has nothing to do with Vladimir Putin or election interference, which is what a lot of Americans think about now when they think about Russia, or about doped-up gymnasts, or old women standing in line for moldy potatoes, or rambling 1,400-page novels about people with really long names.

The ongoing state of poor relations between the U.S. and Russia (and before that, the USSR) has really given us some horrible stereotypes.

Those are stereotypes that Goldstein, a scholar who has been traveling to Russia as often as she can manage it for nearly 50 years, wants to dispel. In her introduction, she acknowledges that this is a somewhat fraught time to be publishing a Russian cookbook. (When she published her first book in 1983, The New York Times canceled its review because a Korean plane had recently been shot down in Soviet airspace and the editors found the subject of Russian food too controversial.) But this is not a book about Russian politics. Instead, it’s about Russian food and life. “The Russia I describe here,” she writes, “is a place not seen by Americans on TV or on tourist trips devoted to the country’s major cities.... Having endured more than their share of horrific regimes, Russians are highly adept at devising ways to lead emotionally rich lives despite oppressive politics and sometimes-murderous government control. They define their lives not by their current autocrats but by the rhythms of the seasons and of the domestic sphere, of growing gardens and foraging, of time spent with dear friends and family.”

In Beyond The North Wind, she tells stories about delicious meals made in communal kitchens from unpromising ingredients, the sharing of delicacies obtained after long hours of waiting in line, clandestine midwinter picnics eaten standing up in the snow with nips from a bottle of vodka for warmth. Over the years, she saw the Communist state crumble—signified by the disappearance of the old ladies who used to sweep the streets of Moscow with little twig brooms—and the rise of capitalism—signified by the appearance of cafes with plentiful European-style food.

She also takes pains to describe what Russian food is not. It’s not the Frenchified banquet dishes imported by Peter the Great during his own great leap forward in the 18th century, and it’s not the mayonnaise-drenched convenience food of the Soviet era. Goldstein here is talking about Russian home cooking, primarily from the northwest part of the country near Scandinavia, though she does make a few exceptions, notably borscht, which is Ukrainian. Russian food is foraged mushrooms, homemade pies and pickles, horseradish and mustard, black bread, fermented everything, covered with lots of sour cream. The primary flavor is sour. The preferred sweetener is honey. It’s diametrically opposed to soft, sweet American food.

Beyond The North Wind is just as much a book about the traditional Russian way of cooking as it is a book of recipes. Goldstein includes informative historical sidebars in every chapter, about Peter the Great, about Soviet cuisine, about the old-fashioned wood-burning stove large enough for lazy people to nap on, about the Russian passions for fermentation and honey. This is an older, quieter Russia than the one you read about in the newspapers, and I’m quite glad I got to spend time there.

As for the food: these recipes take time. I didn’t try any that required fermentation because many would have needed to sit for three or four weeks. Several others that sounded interesting to me required canning equipment (kvass), raw milk (varenets, described as baked cultured milk), or a convection oven (pastila, a cloud-like dessert that was said to be Dostoevsky’s favorite). But even something relatively modest, like blini, buckwheat pancakes, had to sit on the counter for an hour and a half so the yeast could develop.

I had been most excited to try blini, mostly because it’s one of the first Russian foods I had ever heard of but also because I find pancakes delightful. Blini are flatter and more savory than an American pancake and, at least according to Goldstein, they haunt Russians’ dreams so often that entire sections of dream-interpretation books are devoted to them. The buckwheat gives them a nutty flavor, and butter perks them up quite a bit. I’d imagine sour cream and smoked salmon would as well. (I can’t afford caviar.)

I also made a scallion pie because Goldstein said it was her go-to winter Russian pie. It has a rye flour crust, which makes it taste heartier and more substantial than the white flour crusts I’m used to; a little of this pie went a very long way. The filling is scallions (naturally), parsley, and hard-boiled eggs. It tasted like a very green egg salad. It also lasts a very long time; I ate parts of it over the course of three days. I realize this is not a ringing endorsement. There was nothing wrong with the pie itself—I assume it tasted the way it was supposed to. It was a new flavor for me, one I didn’t end up liking, but I was also glad I got to try it.

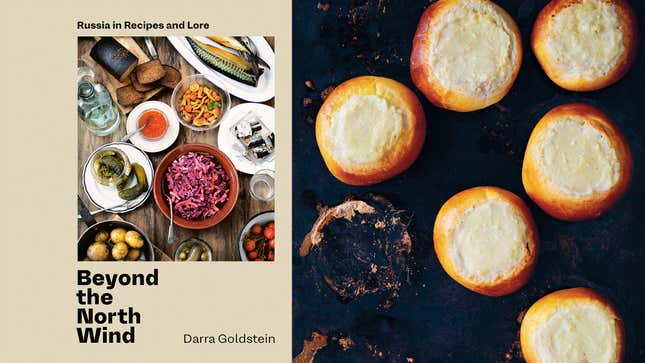

I liked the vatrushki, sweet cheese pies, much more. (Blame my sweet-addicted American palate.) A taste of them, Goldstein writes, brings her back to Soviet times when they were one of the few foods that she could buy fresh, from a bakery in Moscow. “The aroma of baking bread wafting into the air conveyed all the comfort that was lacking in my everyday life.” Vatrushki are less a pie than a sweet roll, with a yeasted dough base with a small indent filled with sweetened farmer’s cheese. I don’t think mine rose enough—they didn’t look like the photo in the book, in any case—but they still tasted very good and went well with a cup of coffee.

One small quibble with this book: although Stefan Wettainen’s photography is beautiful, many of the recipes lack pictures, so if you’re unfamiliar with a dish, it’s sometimes hard to gauge what it’s going to look like when you’re done putting it together. This does create a certain sense of adventure, but if you’re an anxiety-prone cook like me, a bit of fretting and Googling. (What did people do with unfamiliar recipes before the internet?)

I’m still planning to explore Beyond The North Wind a little more. Specifically, coulibiac or kulebyaka in Russian, a fish pie that Craig Claiborne, the longtime New York Times food critic, called “the world’s greatest dish.” I’d been curious about it since I first read an article in The New Yorker several years ago about Daniel Boulud’s quest to recreate it. The kulebyaka Goldstein presents here is a Russian home-cooking variation, simpler than the classic Escoffier coulibiac that called for a dozen foods wrapped in other foods, some quite rare and expensive, and encased in a puff pastry crust. I feel like a taste of it will transport me to another place and time, the way the blini, scallion pie, and vatrushki did. That is what cookbooks, at their best, can do, and that’s what makes Beyond The North Wind incredibly valuable to anyone who’s the least bit curious about Russia beyond the politics.